A bad week in the shop

Published 9 Dec 2019

In this week’s post I spend a lot of time reviewing an incident where a guitar I was working on was damaged by someone else in the shared workspace I use, how I dealt with it in terms of repair, working with the client, and how this impacts my future builds. And as a lighter note, I wrap up with some notes from having spent a bit more time playing with generative design in Fusion 360.

Please also note that in the following I’m going to be fairly critical of trying to build guitars to a particular standard (or anything that warrants a high degree of quality finish) in a maker-space like the one I use. In no way do I think these issues are unique to working in Cambridge Makespace, it’s just a broader issue of using this kind of space for the type of work I do. Note also I’m not trying to be critical of the spaces themselves, just I think there’s limits to their appropriateness for what I do, and I’ve just smacked straight into said limits at full speed. Makespace has been very supportive of my endeavours and always tried to give me the best space for what I do, for which I’m hugely grateful, but at some point the different between what they can reasonably offer and what I want to achieve inevitably diverge, and this post is mostly about that divergence.

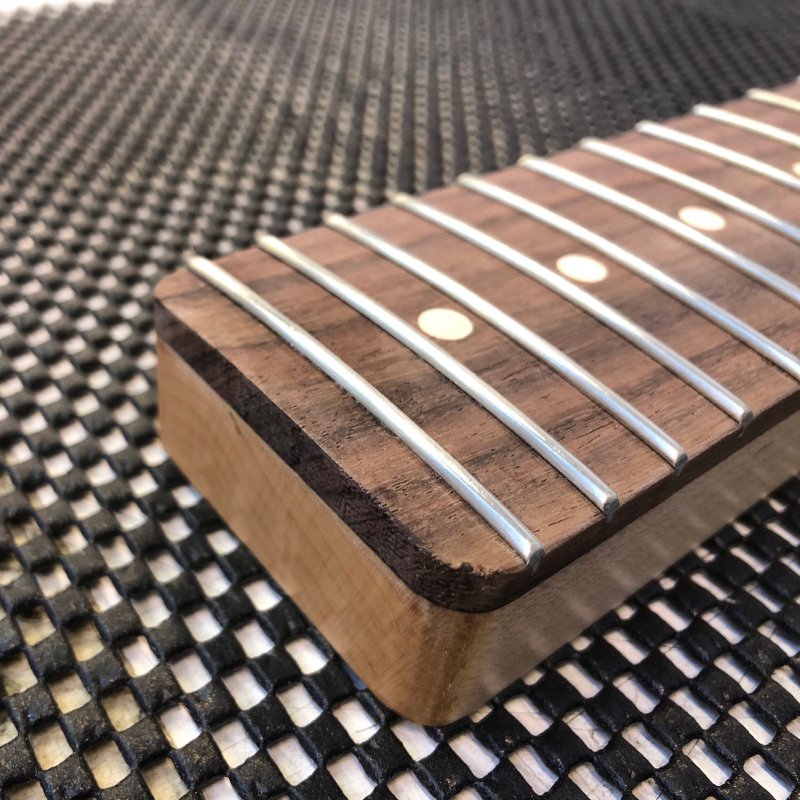

At the end of last week I finished oiling the body and neck for commission #10, and everything was looking lovely:

Unfortunately when I arrived back in the workshop on Monday, I discovered that disaster had struck: whilst the neck was hung up in the workshop to dry from the final coat of oil, someone appears to have taken it down, dropped the neck, and then put it back, causing quite a bit of surface damage to it. It was dented in a total of 6 places, of which 4 were quite notable: two on the headstock, where the straight lines meant they were very visible:

and

and two on the fretboard, one of which is going to be notable when playing:

and

That last one doesn’t look so bad in the picture (my mind wasn’t really on taking top notch photos at the time, sorry), but was the worst in terms of damage to material: it was where the neck must have landed, so the deformation due to impact was the greatest.

Now, these may look minor, but to me are major issues. To make building guitars viable I have to charge what to most people is quite a lot of money: whilst it’s a lot less than what most “proper” custom builders charge, I’m aware its a significant investment for most people. So when I ask people to pay that amount of money, I demand of myself that they get the best in return. No one should be paying the better part of two grand to get a guitar with a neck that’s been dinged and patched up, that’s just not on.

I was quite heart broken when I discovered the damage if I’m honest: regular readers will understand just how much effort goes into building a guitar neck. When I discovered this it was literally the day before oiling was completed and the guitar would be moved to a case and never be exposed to this sort of thing again, which made it all the more unfortunate. As the end of production nears, and you have so much sunk cost in the instrument, I get more and more nervous about things like this, that to have it happen is a nightmare come true.

A few people have asked did I find out who did this and gave them what-for, but I’m not interested in that, as there’s nothing actionable that can come of that: what’s done is done, and most likely the person who is responsible didn’t meant for this to happen, it was an accident. Ultimately this is all my fault, by choosing to do work to a high fit and finish in a place surrounded by people who don’t understand what’s involved and have no direct care/investment in not seeing that undone. I’ve no one to blame but myself.

Makespace, like most maker spaces, is a place to come and have a go, have a bash at something, trying things out, etc. The ethic of a place like this is things are generally fair game as long as you’re not proactively damaging things or mis-using equipment. That means people don’t understand how precious to me (and my client) that neck (or any other bit of a guitar I’m working on) are when they just go to pick them up to have a look, and it’s actually unreasonable given the context of maker-spaces for me to expect them to do so.

Says the voice of hindsight.

I do know this already to some degree, and I don’t generally leave guitar bits out where people can get them, but when they’re being stained and oiled I have no choice. And even though I put them out of the way, ultimately they’re still a thing that people will see as shiny and want to look at.

This incident has taught me that whilst I’m a great proponent of the community workshop, and without it I’d not have achieved the progress I have, I definitely think I’ve pushed the limits of what can be achieved on the custom guitar building front in this environment, and have now paid the price for it heavily (figuratively and literally, as you’ll see below). The question then is, what can I do about it? This is something I need to reflect upon over xmas, and I have some thoughts, but what I’ve done to date clearly can’t continue. Either I need to find a way to change the space I’m in to make room for the kind of work I do, or I need to find somewhere else to at least do the more careful and detailed part of what I do. I can’t make promises to clients that I can make them wonderful instruments in this environment, that is clear, so I need to change something.

Having slept on the incident, I contacted my client as the next step. At this point I didn’t have a good strategy for how to repair the damage, and the guitar was so close to due that whatever I did to fix it would be yet more delay on an already late build, so I just wanted to keep the client in the loop as a matter of principle.

After some discussion we settled on a plan that I would try to fix the neck as best I could, and assuming it wasn’t too bad, keep using that neck. But in doing this I felt I had to give them the guitar at a discount to reflect that this was no longer an “as new” instrument, even if I could make it look close to pristine. this highlights another reason I can’t continue with builds as they are - it’s impacting my take home pay now.

I mostly make my money doing software contracting, but this month as I knew I had a guitar to finish and I knew there was income derived from finishing that I deliberately took fewer contract hours in December, relying on the guitar money to make up the balance: obviously I’m now getting less money, and I will be left short for my December earnings.

Now, I don’t expect you all to cry me a river over this, as a contractor I always try maintain some financial buffer to allow for the variance in work,, and I’ll just have to spend more time on software contracting over the coming couple of months to make up for it. But I know people read this thinking about trying to build guitars themselves, or as part of using a shared workspace, so I just want to emphasise that things going wrong in these shared spaces can have serious consequences if you’re trying to make your living from them. These things will happen, I just want to flag my incident here as an example fo why you need to prepare for bad things to happen if you’re trying to make some part of your living this way.

So, enough moaning for now, what can we do about this damaged neck? I initially assumed that given material has been removed, I had two options open to me: remove more material to make everything match again, or add more material in the form of patching the dents using the old sawdust and wood glue mix approach. Neither of these appealed.

Adding material back via the sawdust and wood glue approach doesn’t work on light woods in my experience, the end result looks too obviously patched, so that ruled it out on the headstock. On the fretboard the dent was on rounded areas that I’d have to rebuild and reshape, and I didn’t really believe the result of me trying to do that would be acceptable either.

So that left removing material, which is clearly also not ideal: I already had things the right shape, so removing material will just make them the wrong shape, and risk in areas them not feeling or looking right.

Thankfully, fellow Makespace member Graeme came to my rescue (yet again), by sending me a link to this video on how to repair dents in wood:

The basic idea is that wood works a bit like a sponge, so if you have a dent where the wood has been compressed, using water and steam you can cause it to expand again. This may not get you back to perfect, but should mean you have less damage to undo. In the video the man uses water and a clothes iron (which I also used), but if you have a clean soldering iron tip you could also use one of those.

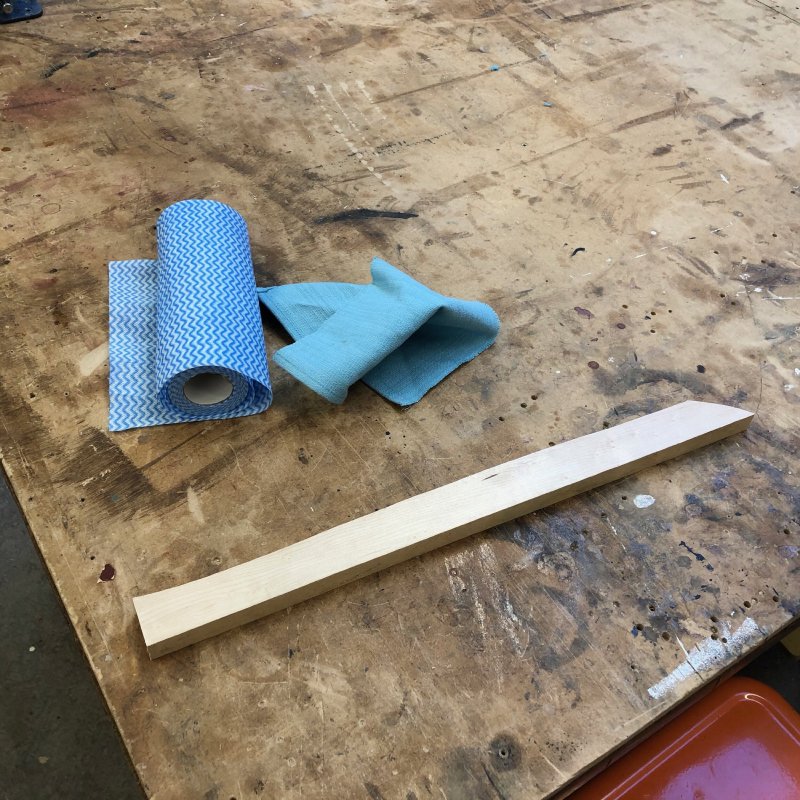

As ever with a new technique, I tested it out on some off-cuts first. I first found some of the maple that I used to make this neck, and prepped it do have some nice sharp, clear edges like the headstock has (or had…):

I then went and found a nice hard edge on a vice in the workshop, and recreated the problem with two dings, one light and one hard:

The next step was to apply warm water to see how that goes. I ran the hot tap in the kitchen until it was just at the bearable to touch level for this:

The result of this was you could already see the dents softening out - it’s working!

However, they’re still quite visible. So then I upped the game by applying more water and then the tip of a clothes iron set to the highest setting, and suddenly it’s like magic:

Here you can see that one dent has pretty much entirely gone by now. There’s a little discolouration, but that’s because the iron I was using turned out not to be clean. The second dent is still visible, and that’s because it’s not just compressed, I managed to hit a sharp edge that broke the wood fibres, and this technique can’t magically fix that. So there’s a limit to this method: it’ll work wonders on compression damage, but not areas where the wood has been cut, torn, or split.

A little light sanding later:

You can still see a slight mark from the second impact damage, but the first is totally gone.

So, if in future you have a dent in the wood thing you’re working on, this is a technique worth trying to bring it back to shape. I often joke that difference between software engineering and woodworking is that in woodworking you can’t hit undo - apparently that’s not always the case.

Having proved the technique in theory, I then turned to the actual guitar neck that had been damaged. The first thing I had to do was gently sand off the oil that I’d carefully applied last week around the effected areas, so that the water could penetrate into the wood. I then repeated the exact same technique using hot water and the tip of a clothes iron.

On the straight side of the headstock we went from this:

to this:

and on the transition side, where it’d be much harder to reshape using subtractive methods, we went from this:

to this:

And after a light sanding you just can’t tell the headstock was damaged. It’s totally mind blowing, and I’m hugely grateful to Graeme for his pointing me in this direction.

I repeated the same technique on the fretboards, and it worked well on the dent on the edge on the fretboard, but could not work miracles on the corner where the neck first landed, that was improved but still not the original shape. However, that i’ve just reworked both corners to flow and be equal and now it looks okay.

The end result? I need to finish re-oiling the neck, but right now you’d not actually know I suspect that anything had gone awry. However, it isn’t the original design I wanted, due to having reshaped the heel slightly. So, it’s a good outcome given the circumstances, but it’s now how I want my builds to go.

The next steps are to finish re-oiling the headstock (which I can do keeping the neck out of the main Makespace workshop) and then it gets into a guitar case and I can relax a bit more. From there it’s the electronics and the pick-guard to finish up.

Unfortunately this week I won’t be in the workshop much due to a funeral I need to attend in another part of the country; my Gran unfortunately passed away last week, so it’s not been the best of times, and the commission will need to resume the week after as I race to get it done before I have to travel for xmas (it never rains, etc.).

To end on a more positive note, and follow on from last week’s notes on the topic, I’ve been playing some more with Fusion 360’s generative design, particularly given it’s free to use all of December.

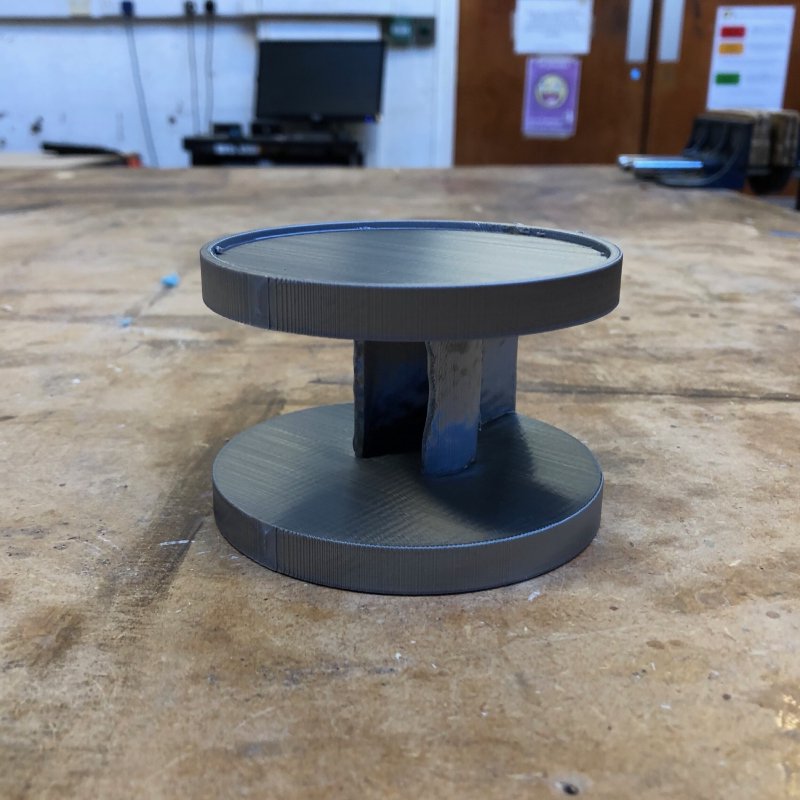

Firstly, I did a 3D print of the cup platform that I designed last week:

It can join the shelf I have of “first thing I made using…” items. It was interesting to note that despite it not being designed for printing with an ultimaker, the result is really quite sturdy. Alas, I printed it with PLA, which melts at 60˚C, so not something I can actually put a cup of tea on :)

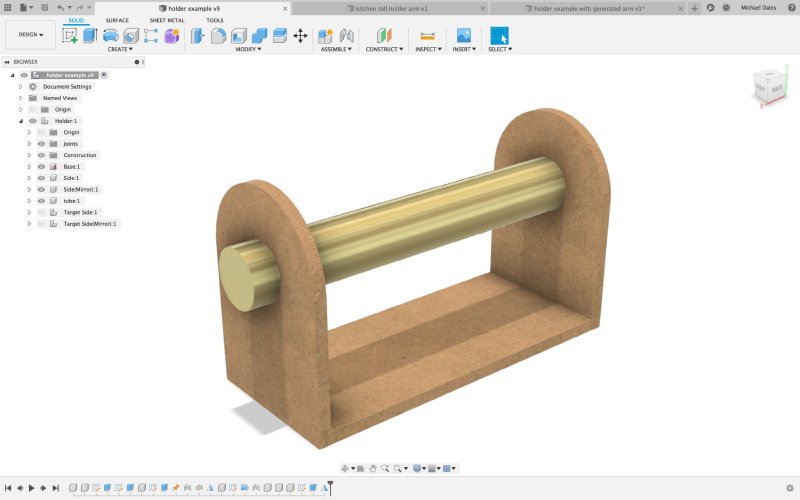

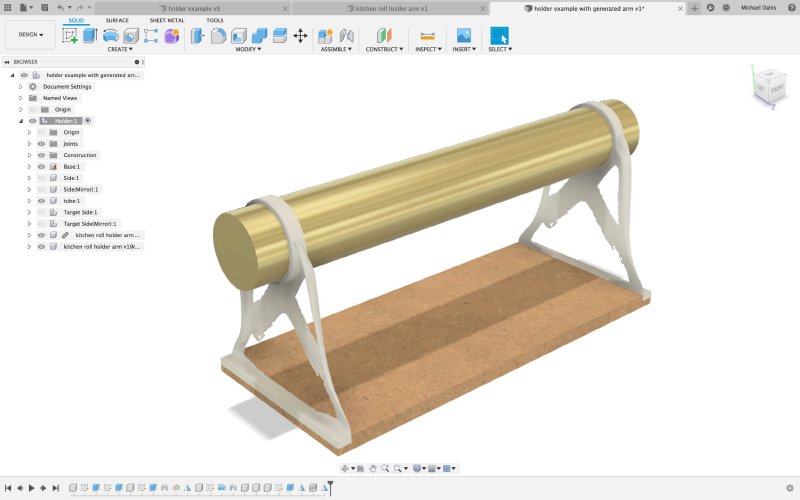

I also was teaching my occasional Introduction to Fusion 360 class at Makespace at the weekend, so I decided to apply generate design to that. During the class I get everyone to follow along and design a kitchen roll holder:

So for fun I got Fusion to generate some new minimal volume arms for this:

Quite funky, but also not quite up to the task. The arms here do work, but only in the way I asked, not the way I needed. Like with anything involving computers, generative design will only do what you ask it to do, and here I’d explained about the weight of the kitchen roll, so the arms will support that. But what I’d not explained about was the sideways forces when you insert/remove the tube, so the arms are incredibly thin at the bottom and flex sideways quite happily.

Still, that in itself was a useful lesson. I’m used to using Fusion 360 to make things where I know that everything is over specified and safe under the stresses, so I wasn’t thinking like I do when I’m writing software - like an engineer! What are the forces here? Not just the obvious ones such as load when static, but also what’s the load when someone changes the kitchen roll? What’s the load when someone tugs on the roll to get a sheet? What else can go wrong? You need to ask so many questions in any engineering discipline, but for the things I make in the workshop by-and-large I don’t need to ask these things in terms of structural rigidity as someone else has already thought of them. For generative design, I need to update my mental model! So, I’ll be generating more of these soon, but with a many more constraints.